US shares did well in January. Stay away.

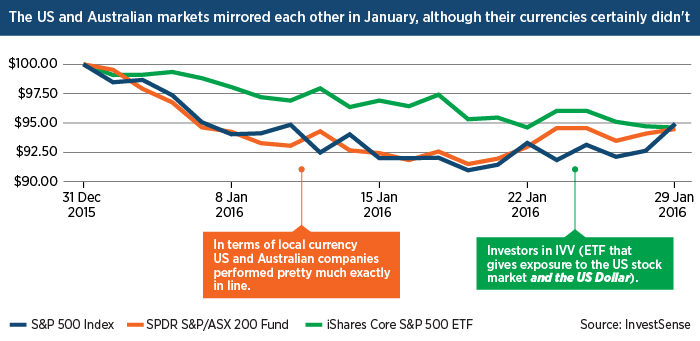

Markets suffered a fairly torrid start to the year, but many who had exposure to the US stock market may have been feeling slightly smug. Investors in IVV, the locally listed ETF over the S&P500 index, have missed the worst of it, certainly in the first few weeks when the Australian market was down by almost 10%. IVV missed half of that fall.

However, investors should be clear that this was solely due to the weakness of the Australian dollar as commodity prices continued to fall. As commodity markets bounced in the last week and markets rose, so the difference disappeared again. We discussed a similar dynamic that played out during 2015 a few weeks ago, but in January there was an important difference.

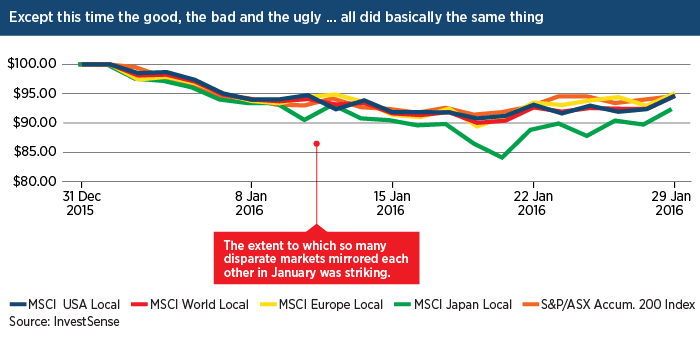

Markets seemed not to care how a slowing China would variously affect companies in different regions. Countries with weaker economic ties to China fell by as much as the others. Do markets believe that the implications of a Chinese implosion goes beyond its existing trade partners? Or alternatively are the exporters to China (like Australia) already bombed out, and much of the downside is already priced in? If it is the latter then it is quite encouraging for the local market as the basic valuation driven thesis that we outlined last week would seem robust.

If, however, markets are worrying about an uncontrolled seizure of credit markets and global trade emanating from China, then we would have to be a bit more circumspect about our banks. Remember, they still represent a large part of our dividend receipts. For now we would err towards the thesis where Australia looks like good value, with reasonably solid dividends and plenty of upside if global growth unexpectedly ticks up.

However, we have more serious concerns for the long-term outlook of US share investors. Following that same basic valuation framework, we can see that:

- US companies in aggregate currently pay around $2 in dividends for every $100 you invest. You can add another $1 to your expected return due to cash returned to shareholders in the form of buybacks (instead of paying dividends companies buy their own shares, which should immediately lift the price of shares by a similar amount). This equates to a base case return of around 3% before accounting for growth in dividends or long-term changes in other investor’s appetite for US shares.

- Long-term growth in dividends of around 2% has risen since the GFC to around 5% (excluding the effects of inflation). This is unsustainable over the long-term as dividends can’t grow by more than the growth in the underlying economy, which has grown by around 3% but has struggled to grow above 2% since the GFC. In fact dividend growth more often tends to lag economic growth over the long-term by about 1%. A sizable post-GFC debt burden and an ageing population are expected to restrain growth into the foreseeable future. Just as US companies have been paying a higher proportion of earnings as dividends, the growth in those earnings appears to be slowing from its cyclical high. This suggests that adding more than 2% long-term growth to that base case would be very optimistic and that there is considerable downside to even that modest number.

- Lastly, US shares have been well supported in recent years as the economy has been seen as a bright spot. By most measures the market now looks expensive: we think investors are paying 10-20% too much for that stream of dividends. If investors start questioning the viability of that dividend growth (for instance due to a downturn in the business cycle), that could detract 1–3% from the growth in share prices over the next 10 years.

Putting all this together, we can see very probable scenarios where investors get paid a measly 2% per annum for holding quite risky US shares over a very long period. There are also some very possible scenarios where long-term returns could be significantly negative over a 10-year horizon (for instance, if dividends fall and investors become overly pessimistic). From a valuation standpoint this looks very much like 2000, 2007 and maybe the late 1960s, so there are some fairly unpalatable precedents.

Could all this continue to be outweighed by currency movements? Over the long-term we don’t think so, not least because the Australian dollar is probably much closer to ‘fair value’ than it was. Last year also showed just how wrong you can be with currency forecasts (not one economist out of about 70 forecast that the Australian dollar would go below 70 cents per US dollar a year ago). We don’t think that would make for a very solid long-term investment thesis although the US dollar does remain defensive and this is a good reason to have some US dollar exposure in your portfolio.

US companies now account for around half of most overseas portfolios. So while the nuts and bolts of valuation may feel esoteric, this presents a significant risk for investors who naturally seek to diversify from a concentrated local market with uncertain prospects. It is also why one of the largest positions in the InvestSMART Diversified Portfolios is the underweighting of US equities and why we are actually a little overweight local shares.Frequently Asked Questions about this Article…

US shares seemed to perform well in January mainly due to the weakness of the Australian dollar, which helped investors in the IVV ETF over the S&P500 index avoid the worst of the market downturn.

The Australian dollar's weakness can make US investments appear more favorable, as it did in January. However, this effect can be temporary and may not provide a solid long-term investment strategy.

Long-term concerns for US share investors include unsustainable dividend growth, high valuations, and potential negative returns over a 10-year horizon if dividends fall and investor sentiment turns pessimistic.

US companies currently pay around $2 in dividends for every $100 invested, with an additional $1 from buybacks. This results in a base case return of about 3% before considering growth in dividends or changes in investor appetite.

No, the current dividend growth of around 5% is considered unsustainable over the long-term, as it exceeds the underlying economic growth, which has struggled to grow above 2% since the GFC.

US shares are seen as overvalued because investors are paying 10-20% too much for dividend streams, and any downturn in the business cycle could detract 1-3% from share price growth over the next decade.

Currency movements, like the Australian dollar's weakness, can temporarily boost US share investments. However, relying on currency fluctuations is not a solid long-term investment strategy.

Having a large portion of a portfolio in US shares poses a risk due to high valuations, potential negative long-term returns, and the need for diversification from a concentrated local market with uncertain prospects.