Investing: Like parenting, but hotter

When I told Tony Kaye, editor of Eureka Report, this week I was going to write about the similarities between investing and parenting, via a story about our biggest recommendation failure of the year (so far) and chilli sauce, his expression said it all.

Dosed up on Codral and coffee, I’m going with it anyway. If you don’t like the result, please direct all complaints to Tony, who will offer sage nods, a sympathetic ear and the likely riposte that “at least you don’t have to work with him”.

On the winter nights in the months after my first son was born, I would stuff him into a Swedish baby pouch and walk down Macpherson Street in Sydney’s eastern suburbs. It was one of the few ways to get the little bugger to sleep, and my route had the advantage of passing an Indian takeaway.

Overcome by hunger and sleep deprivation, on the way home one night I hooked into a few pakoras, liberally dosed with hot sauce. Always a messy eater, I should have anticipated the result, quickly noticed by the mother on our return. The matted, greasy hair on the boy’s head was less of a problem than the chilli-coloured burns on his hands and arms.

A few bath time scrubs removed the discolouration but the parenting mistakes have continued pretty much unabated. Everyone’s learning on the job, which inevitably means getting it wrong. Despite this, there is still no sign (as yet) that in my case regular occurrences akin to the pakora incident have had a lasting, adverse impact.

So much for the airing of my personal dirty laundry. Let’s tuck into the professional stains and try to learn something from them, starting with our worst Buy ever.

On April 10, 2007, Timbercorp joined our Buy List at a price of $1.85, a rare Strong Buy. Two years later we advised members to sell at a price of 7.2c, a loss of 96 per cent. Had we waited another six days when the company went into administration, it would have been 100 per cent.

Against that backdrop, the 67 per cent loss we crystallised on financial software house GBST the week before last looks merely abject. In the interests of full disclosure, I’m a GBST shareholder. We eat our own cooking here, maggots and all. And if that didn’t put you off your brekkie, maybe this will:

GBST isn’t an aberration. There have been many stocks on which we’ve lost good money. Software company Infomedia was a 70 per cent loser. Gold miner Croesus suffered a Timbercorp-like total wipe-out, which I subsequently called my greatest investing mistake. Although still a Hold, Santos is down 75 per cent since our first Buy in 2009. Between 2003 and 2006, ROC Oil almost tripled in price and then collapsed. By 2009, members had suffered a 60 per cent loss when we sold out.

The list goes on. Right now, iCar Asia remains a Hold but is still down 76% on the original Buy recommendation. Sigma Pharmaceuticals, meanwhile, suffered an 81% loss in a mere three years. QBE Insurance is particularly memorable. From the initial recommendation on 5 Aug 11 to a downgrade to a Sell on 29 Jul 14, members lost only 28%. The fact that it was one of only five Strong Buys in our history intensified the pain. Even worse, we’ve recommended plenty of stocks that have crashed and missed even more that have skyrocketed.

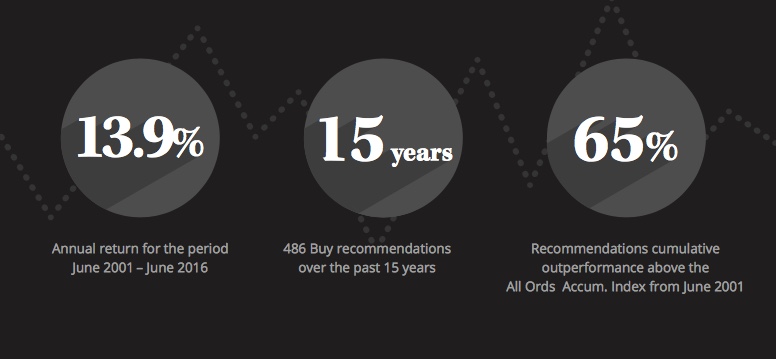

By now, I may have convinced you that we have absolutely no idea what we’re doing. There is chilli sauce all over the place. But then there’s this from our 2016 Recommendations Report (the 2017 version, independently audited by Grant Thornton, is imminent):

In the 15 years between June 2001 and June 2016 we made 486 Buy recommendations, delivering an annual return of 13.9 per cent. That’s a 65 per cent cumulative outperformance above the All Ords Accumulation Index.

What does that mean? Well, $100,000 invested in the All Ords on June 1, 2001 would have produced $432,000 by June 30, 2016 (including dividends). Had members followed all our recommendations – Holds, Sells and Buys – at the time we made them over the same period, that sum would be worth $712,000 – a difference of $280,000. So, it matters.

The same performance effect shows up in our equity income and growth portfolios, both of which have outperformed their benchmarks substantially. Which begs the question: How can one make so many stuff ups and still get a good result?

Let’s return to the analogy. The priority in raising children is to provide for their health and safety. It’s no use making good decisions if they’re not around to benefit from them. It’s not so different in investing. Your first objective shouldn’t be to smash the index, but rather to keep yourself in the game.

Parenting and investing are exercises in risk management. Both demand we acknowledge that the future is uncertain and mistakes are inevitable. In a harsh and capricious world, good risk management starts with not driving the kids home drunk without seatbelts. In investing, it entails avoiding anything that might blow up your portfolio, sending you off to Centrelink wondering where your shirt is.

It took Intelligent Investor a while to learn that lesson. Our analysts, schooled in the art and science of value investing, understood it implicitly. Our mistake was in thinking our readers understood in the same way that we did.

Instead, readers were imputing a degree of confidence not just from the recommendation itself but the way our research was expressed and its frequency of coverage, the result of which was never more painfully clear than with Timbercorp. Between April 2007 and September 2008 we reiterated our Buy recommendation 16 times. These were perceived additional votes of confidence and readers loaded up, way too much as it happened. When the crash came, it really hurt.

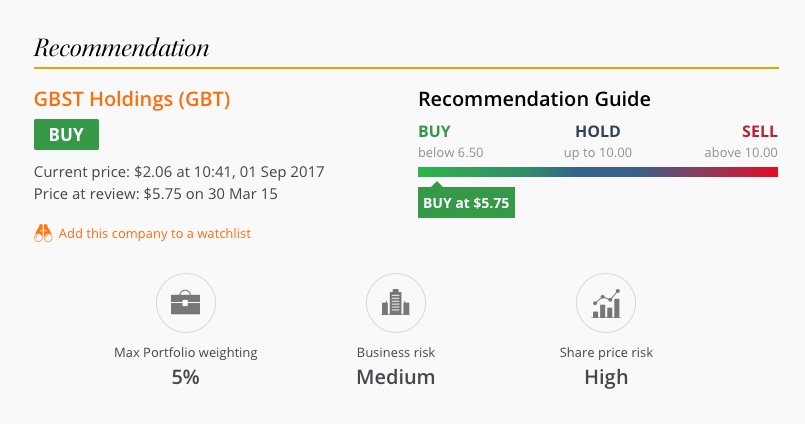

That oversight was addressed with the introduction of what you now see before each piece of Intelligent Investor research. Here’s an example from GBST at the time of our original Buy recommendation in March 2015.

Now, let me guess. You looked at the word ‘Buy’ in the top left first and then glanced across to the recommendation guide. Nothing wrong with that, if you then examined the three grey icons at the bottom afterwards. If you didn’t, then you’re in danger of missing out on the free insurance policy.

These icons are interlinked. At the time of this GBST recommendation, we viewed the share price risk to be ‘high’ and the business risk ‘medium’. Given these risk ratings, we recommended members allocated no more than 5 per cent of their portfolio to the stock.

That’s why we’ve managed to make so many mistakes and still beat the index. A 67 per cent loss sounds like a disaster, but if you followed our maximum portfolio weighting, the damage to your portfolio is only 3.5 per cent. Our long record of winners has easily outweighed poor performers like GBST. What else can we take from this potted history?

- Portfolio weightings matter. No parent lets their children play with knives. Having just a few stocks in your portfolio is playing with knives. Ensure your portfolio is not overly exposed to any one stock or sector.

- Accept loss. No child grows up without a few cuts and bruises. But only a foolish parent stops a child from climbing trees in fear of a broken limb. Accept the risks in investing and the losses that result.

- Think of the upside. Your very worst investment will cost 100 per cent of your stake. Your very best might return 1000 per cent. Loss aversion means you’re more likely to remember the former than the latter. Next time you think of a stock that has cost you, think of the many more that have made up for it and then some.

- Demand integrity. The finance industry knows how hard it is for clients to do as I’m recommending, which is why it crows about its successes and buries the failures. Next time you get the opportunity, ask your adviser to show the kind of openness and transparency you get here. Tell them it builds trust and that only being open about failure earns the right to brag about success.

Frequently Asked Questions about this Article…

Investing is similar to parenting in that both require risk management and learning from mistakes. Just as parents aim to provide for their children's health and safety, investors should focus on staying in the game and managing risks effectively.

Investors can learn that mistakes are inevitable, but managing risk and diversifying portfolios can mitigate losses. Accepting losses and focusing on long-term gains is crucial for successful investing.

Portfolio diversification is important because it reduces the risk of significant losses. By not being overly exposed to any one stock or sector, investors can protect their portfolios from major downturns.

Investors can manage risk by diversifying their portfolios, understanding the risk levels of their investments, and not over-allocating to high-risk stocks. This approach helps minimize potential losses.

Loss acceptance is crucial in investing as it allows investors to learn from their mistakes and focus on potential future gains. Understanding that losses are part of the investment journey helps maintain a long-term perspective.

Investors can balance risk and reward by diversifying their portfolios, setting appropriate portfolio weightings, and focusing on long-term growth rather than short-term gains. This strategy helps achieve a more stable investment outcome.

Transparency is important because it builds trust between investors and financial advisors. Openly discussing both successes and failures allows investors to make informed decisions and fosters a more honest investment environment.

Portfolio weightings are significant because they determine the level of exposure to individual stocks or sectors. Proper weightings help manage risk and ensure that no single investment can disproportionately impact the overall portfolio.