How to worry better

To our ancestors eking out a living on the land, time was an undulating rhythm, of sunrises and sunsets, one season folding into another. Contemporary life views time more as a resource to be excavated, spent and accounted for.

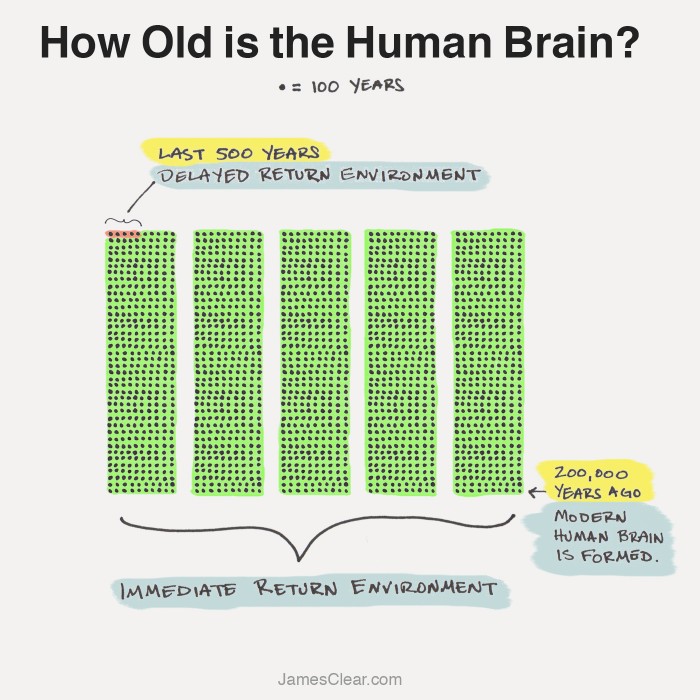

The difference is fundamental. Unlike other animals, humans live in a delayed return environment. The decisions we make today - the stocks we buy and sell, what we do at work and how we berate our children - have no immediate benefit. The pay off, we hope, comes later.

Other animals inhabit an immediate-return environment, where decisions deliver an instant outcome, be it food, shelter, escape, or, in the case of the dogs in my life, a dried pig’s ear. Animals have problems of the present; ours are mainly of the future.

Key points

-

Our brains aren't made for the modern world

-

Stoicism can help

-

Six techniques to reduce anxiety

Dogs do not worry about whether they’ll have enough in retirement and we don’t worry about whether someone will let us out for a pee in the morning. So why do they look so chilled and happy while we’re riddled with anxiety?

Because the human brain has failed to adapt to an environment that is radically different to what it was even a few hundred years ago. Our brains act much like that of a dog, operating in an immediate return environment, whilst the world we inhabit is based on delayed returns.

Source: JamesClear.com

The resulting tension is expressed as a physiological burden. As James Clear puts it in The evolution of anxiety, ‘the mismatch between our old brain and our new environment has a significant impact on the amount of chronic stress and anxiety we experience today.’

This is the principal reason why investing - an archetypal delayed return activity - is so psychologically demanding. It may also explain why successful investing begins with the mastering of our brain’s maladapted plumbing.

This is the focus of what follows. The aim is not to eliminate stress and anxiety but to reduce it to the point where you can still be confident of rational decision making.

The current environment makes this especially difficult. A few months ago, vaccines had come to our rescue. Inflation due to supply shortages and surging economic activity was the worry du jour. This now seems absurd. Delta is a game-changer and the next few months are tailor-made for terrible decision making. The shops are closed, many of us are confined to our homes and share prices are hitting record highs as economic activity tanks.

As John Hussman of Hussman Funds wrote in The folly of ruling out a collapse, ‘It may be the greatest collective error in the history of investing to pay extreme multiples for extreme earnings that reflect extreme profit margins and extreme government subsidies, while imagining that those multiples also deserve a “premium” for depressed interest rates that reflect depressed structural economic growth.’ Or it may not.

For a species predisposed to anxiety, nature is delivering us a bountiful selection of triggers. I have found stoicism - a branch of Greek philosophy practised by Seneca and Epictetus - useful in this regard. In short, knowledge can be obtained through reason and, contrary to Facebook’s operating principles, truth can be separated from falsity.

The method for applying reason to determine truth is a Zen-style unattachment in accepting the world as it is and to not have one’s mind hijacked by greed, envy, fear and other action-distorting emotions.

With these principles in mind, here are a few strategies to lower the worry-o-meter before making an important decision.

1. Contemplate the worst...

If you can get comfortable with the idea that your portfolio might fall 40% in the space of a few days but appreciate the fact that you’ll still be here, eating and breathing, and in with a chance of recovery, you’ll be prepared for the worst and fear it less. This will put you in a better position to take advantage of a crash if the worst materialises.

2. ...knowing that the worst rarely happens

Knowing that the chances of the worst happening are small makes it easier to contemplate. Research published in Behaviour Therapy suggests that 91% of the things people worry about don’t eventuate.

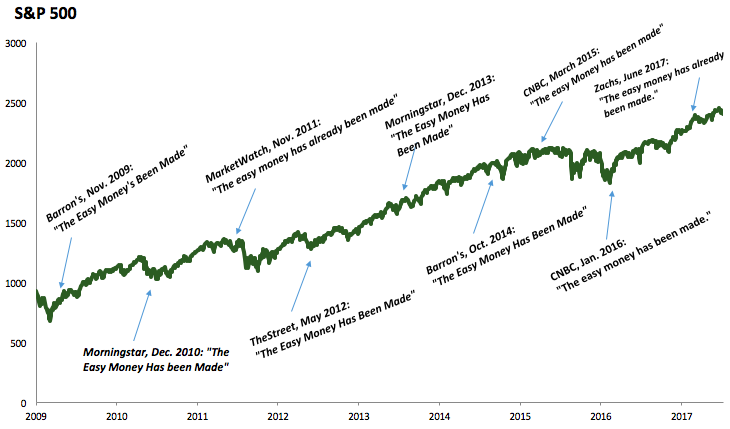

The data set was small but this makes intuitive sense. We worry about those things that might threaten us. Contemplating those threats helps us to get more comfortable with them and knowing that it probably won’t happen relaxes us further. Then you might be in a position to accept that something like this could happen instead:

Source: Morgan Housel

3. Acknowledge what you can’t control

Humans, like markets, hate uncertainty, which is why our brains are permanently occupied running war game scenarios. The future, by definition, is uncertain and no amount of worrying will change that.

I once played beach football with a group of Buddhist monks (these things happen up here), mentioning to one that I worried about the state of the planet we were leaving our children. ‘How much worrying would you have to do to solve climate change?’ he pointedly asked. There’s no point worrying about what you can’t control; focus on what you can. (I returned the humiliation when I nutmegged him before slotting the ball past the keeper’s billowing red and orange robes. Take that monkees.)

4. Allocate time to worry

Let’s face it, none of this is going to stop you from being anxious about something. But what if you made time in your daily routine to actively worry, on the understanding that once that time was over you had to wait until the same time the next day to worry about it again? Think of it as a useful self-deception, a cheat that allows you to live worry-free for most of the day because you've made time for it.

5. Cut out the noise

The more uncertainty there is, the more experts, chancers and ne'er do wells step up to answer it. Even the smartest, most well-intentioned and cautious commentators don’t know as much as they seem but our anxiety is such that we listen to them anyway.

As Ari Fleischer said in an Apple TV documentary on 9/11 recently, ‘If the answers you are seeking relate to things you can’t control, chances are you’re wasting your time.’ There is no obligation to read the newspaper, watch the news or hang out on Facebook, all of which increase their audiences through the marketing of emotion, usually fear. It is neither useful nor healthy, so why not stop it? Exercise, read, take a walk or plant some seeds instead. Who needs sermons from the mountain of the unknowable?

6. Live in the uncertainty and work at it

Investing is hard because it is inherently uncertain. But in the long run it is also meritocratic - in the words of Ben Graham, a weighing machine rather than a voting machine.

If you’re investing for the decades ahead, living in a delayed return environment world with an immediate-return functioning brain, the effort you put in now will compound your knowledge and your returns over the years ahead.

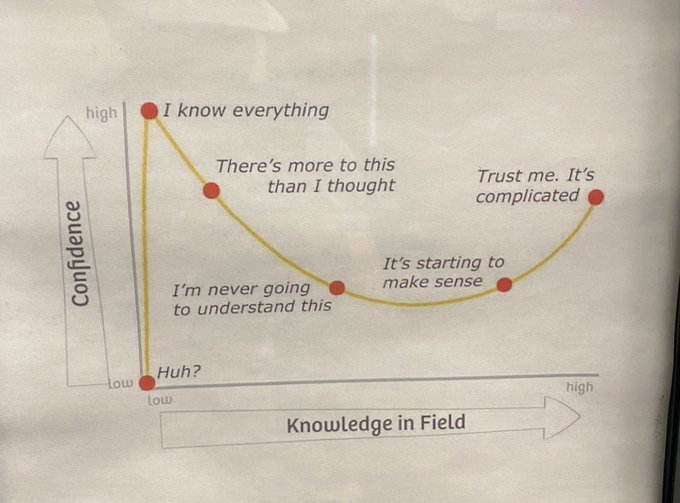

Source: Brent Beshore

Had we not been through the Asian crisis, the dotcom crash and the global financial crisis, we probably would not have acted with the courage and conviction we did in March last year. The accumulation of knowledge proceeds according to the image above. Being humble, managing your anxiety and working at becoming a better investor is how you become a better investor.

Good luck.

Frequently Asked Questions about this Article…

Humans live in a delayed return environment where decisions made today, like investing, have no immediate benefit, unlike animals that live in an immediate-return environment. This mismatch between our brain's evolution and modern life leads to increased anxiety.

Stoicism, a branch of Greek philosophy, encourages accepting the world as it is and not letting emotions like greed and fear distort decision-making. This mindset can help investors manage anxiety by focusing on reason and separating truth from falsity.

Some techniques include contemplating the worst-case scenario, acknowledging what you can't control, allocating specific time to worry, cutting out unnecessary noise, and embracing uncertainty while working on becoming a better investor.

Contemplating the worst-case scenario helps investors prepare mentally for potential downturns, reducing fear and allowing them to take advantage of opportunities if the worst does happen.

Focusing on what you can control and letting go of what you can't reduces unnecessary worry. This approach helps investors concentrate on actionable steps rather than being overwhelmed by uncertainty.

By setting aside a specific time to worry, investors can limit anxiety to a manageable period, allowing them to live worry-free for the rest of the day and focus on productive activities.

Reducing exposure to news and social media, which often amplify fear and uncertainty, allows investors to focus on more constructive activities like exercise or reading, leading to a healthier mindset.

Investing is inherently uncertain, but by embracing this uncertainty and continuously learning, investors can improve their skills and make better decisions over time, leading to long-term success.