ETFs: How to use ETFs in a portfolio

Investors are turning to exchange-traded funds for quick, low-cost diversification, with recent research showing an 11% year-on-year increase in the number of Australians using ETFs to 202,000, including 83,000 self-managed super funds.

There are still a few out there with reservations, however.

Of the respondents to the BetaShares/Investment trends 2015 Exchange Traded Funds report who were planning to use ETFs for the first time in the next 12 months, the main reasons put forward as holding them back were a general lack of knowledge about ETFs or how to use them in a portfolio.

A SIMPLE APPROACH

ETFs may seem a bit mysterious to some investors. But they’re really very simple.

Most active investors place their faith in shares in Australian companies, so their knowledge of the investment is backed up by the familiarity with the brand. The actual shares they own may not seem that tangible, as numbers on a screen, but owning a small slice of a major bank, for example, means something when you see its branches and advertising every day.

When you buy units in an ETF you aren’t investing in the provider — huge investment companies such as BlackRock (which offers the iShares brand), State Street (with SPDR) and Vanguard, to name a few. Instead, your money buys units in a trust fund that owns all the stocks in the relevant index.

So let’s say you buy the iShares ETF over the S&P/ASX200 for about $20.70, the price in early April when the index was at about 4975 points. That means your investment will go up and down in direct proportion to changes in the index. You own the index.

A year or however long later, as companies drop out of the top 200 or enter into it, the provider has been adjusting the fund holdings to mirror the composition of the S&P/ASX200. Your unit, no matter how the top 200 has changed since you bought it, will be priced to the current market.

SAFETY NET

Of course, when you buy an ETF the seller could very well turn out to be an investor just like yourself. So how do you know you’re paying a fair price? Because there is something of a safety net in the system, in that the unit price must track the value of the index, which is derived from the market value of every stock in the index.

The providers police the “tracking error” — the difference between the unit price of the ETF and the value of the underlying assets — by outsourcing the job to “market makers”, specialists who sit there all day jumping into the market if ETF unit prices drift from net asset value.

Market makers are there to make money, like everyone else, but their role in the market is to make sure ETF unit prices stay very close to their true value, the value of the stocks in that index.

This is why an ETF is never “expensive” or “cheap” as Listed Investment Companies sometimes are. It is always the right price, which is determined by the index. The real question is whether the index is expensive or cheap.

HOW TO USE ETFs IN A PORTFOLIO

Australians are most comfortable holding portfolios of direct shares for now, where individuals decide which companies they want to own. Let’s look at a portfolio of Australian “blue chips”, as they’re called, constructed in April 2011 which includes the big four banks, the two biggest miners (BHP Billiton and Rio Tinto), Telstra, energy giants Woodside and Santos, and retailer Woolworths all held at equal weights. Research into the portfolios of self-managed super funds shows they are not dissimilar to that.

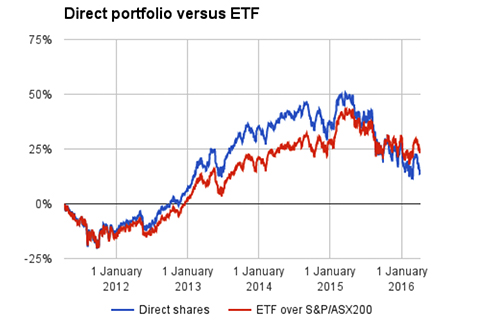

Now let’s compare the outcome for that portfolio of direct shares with the value of one ETF over the S&P/ASX200, where the value is derived from 200 companies.

The portfolio of direct shares was going very well for a long time there, until midway through last year. The chart includes income from dividends, and some of the companies were good picks for yield alone. But the reversal in fortunes between the two strategies over the past year shows the danger of concentration in a portfolio. The 10 companies chosen make up a large chunk of the overall index, and their price movements are responsible for most of the ups and downs for the ETF. When the direct portfolio started to slump, however, the ETF overtook it because the other 190 companies in the top 200 performed relatively better.

Also, the ETF “portfolio” involved one trade, whereas the direct portfolio involved 10. Transaction costs are a drain on returns, so of course it makes sense to keep them to a minimum. The ETF comes with a fee of course, in this example 0.15% a year (using the iShares S&P/ASX200 ETF, with the code IOZ).

SIMPLE AS THAT

Australians are catching on to ETFs, but they are still nowhere near as popular as they are in the US or Europe. In the US, trade in ETFs accounts for about a third of total sharemarket volume. They have become popular because they allow cheap, simple diversification (far fewer transaction costs, for a start). A big benefit to Australian investors is the ability to own global companies via offshore indices, including the S&P500 in the United States. That brings the risk of currency changes, which can also be a benefit if our dollar weakens.

The menu of global ETFs available on the ASX is growing all the time. Deciding which ones match your objectives is not a straight-forward task. But that’s another story...Frequently Asked Questions about this Article…

Exchange-traded funds (ETFs) are investment funds that trade on stock exchanges, much like stocks. They are popular because they offer quick, low-cost diversification, allowing investors to own a slice of a broad index like the S&P/ASX200. This means you can invest in a wide range of companies with just one purchase, reducing transaction costs and simplifying portfolio management.

ETFs provide diversification by allowing investors to own a broad range of stocks within a single fund. For example, an ETF tracking the S&P/ASX200 index includes shares from 200 companies, spreading risk across multiple sectors and reducing the impact of poor performance from any single company.

ETFs are generally more cost-effective and easier to manage than direct share investments. With ETFs, you make a single trade to gain exposure to a broad index, minimizing transaction costs. In contrast, managing a portfolio of direct shares involves multiple trades and higher transaction fees. Additionally, ETFs have lower management fees, such as the 0.15% annual fee for the iShares S&P/ASX200 ETF.

A 'tracking error' refers to the difference between the ETF's unit price and the value of its underlying assets. It's important because it indicates how closely the ETF follows its benchmark index. Market makers work to minimize tracking errors, ensuring that ETF prices stay aligned with the true value of the stocks in the index.

ETFs are considered a safe investment option for everyday investors due to their diversification and the mechanisms in place to keep their prices aligned with the underlying index. However, like any investment, they carry risks, such as market volatility and currency fluctuations, especially when investing in global ETFs.

ETFs can be used to invest in global markets by purchasing funds that track international indices, such as the S&P500 in the United States. This allows Australian investors to own shares in global companies, providing exposure to international markets and potential benefits from currency fluctuations.

The potential risks of investing in ETFs include market volatility, as the value of the ETF will fluctuate with the index it tracks. Additionally, currency changes can impact returns when investing in international ETFs. It's important for investors to understand these risks and consider them in their investment strategy.

Some investors might be hesitant to invest in ETFs due to a lack of knowledge about how they work or how to incorporate them into a portfolio. Despite their simplicity, ETFs can seem mysterious to those unfamiliar with them, leading to reservations about their use in investment strategies.